The Yiddish Language: What’s so special?

by Beny Maissner (originally published at holyblossom.org on January 1, 2014)

A little less than a century ago, Yiddish was the primary language of the vast majority of the Ashkenazic Jewish population, the Jews from Central and Eastern Europe. Mostly a hybrid of Hebrew and medieval German, it borrowed words from the many lands where Jews had lived and has a grammatical structure all its own, although, the alphabet is based on Hebrew characters. Sadly, Yiddish has largely vanished from our Jewish cultural life, a victim of both assimilation and murder. In recent years, however, it has been experiencing an intellectual resurgence, with serious Yiddish Study programs at several universities. And many Jews are seeking to reconnect with their heritage, through this nearly lost language.

The word Yiddish means Jewish language. It is also affectionately referred to as Mame Losh’n, or mother tongue, for being the language of women, children and homelife. This term of endearment is loaded with collective nostalgic memories and stands in contrast to Loshn Koydesh, the Holy Tongue of Hebrew, which was the language of men in study and prayer.

It is generally believed that Yiddish became a language of its own sometime between 900 and 1100 C.E. But it is difficult to be certain, as in its early days Yiddish was an oral rather than written language, and thus, leaves little by way of concrete traces. However, the great Medieval Biblical scholar, Rashi, occasionally used Yiddish words, written in Hebrew letters, when the Hebrew language lacked a suitable term or when the reader might not be familiar with the Hebrew term. This is how written Yiddish is thought to have begun, similarly to our transliteration when we write Hebrew words with Roman characters.

The Yiddish language thrived for many centuries, evolving farther and farther from German with its own unique rules and pronunciations. Yiddish also developed a rich vocabulary of terms for the human condition, to express strengths, frailties, hopes, fears, and longings. For example, there are three terms for suffering: a shlemiel (a person who suffers due to his own poor choices or actions), a shlimazl (a person who suffers through no fault of his own), and a nebech (a person who suffers because he makes other people’s problems his own). But Yiddish is also a language of humour and irony. An old joke illustrates the distinction between the types of suffering: a shlemiel spills his soup, it falls on the shlimazl, and the nebech cleans it up! Without the knowledge of most people, many Yiddish terms have found their way into the English language are used without their historical context.

As Jews became assimilated into the local culture, particularly in Germany in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Yiddish language was increasingly criticized by Jews as a barbarous, mutilated, ghetto jargon, which was a barrier to Jewish acceptance in German society and would have to be abandoned if there was to be hope for Jewish emancipation. Ironically, at the same time that German Jews were rejecting Yiddish, Yiddish was beginning to develop a rich body of literature, theatre and music.

From the earliest days of Yiddish, there were a few siddurim (prayer books) for women that were written with Yiddish transliteration of the Hebrew prayers. The first major work to be written entirely in Yiddish was Tsena uRena (Come Out and See), more commonly known by a slurring of the name as Tsenerena. From the early 1600s, Tsenerena is a collection of traditional biblical commentary and folklore tied to the weekly Torah readings. Like the early siddurim, it was written for women, who generally did not read Hebrew and were not well-versed in biblical commentary. It was meant to be easier than the Hebrew commentaries for men. Two centuries later, in the 1800s, Yiddish newspapers began to appear, including Kol meVaser (Voice of the People), Der Hoyzfraynd (The Home Companion), Der Yid (The Jew), Di Velt (The World), and Der Fraynd (The Friend). There wer ealso socialist publications, such as Der Yidisher Arbeter (The Jewish Worker) and Arbeter-Shtime (Workers’ Voice). Some Yiddish language newspapers exist to this day, for example, Forverts (the Yiddish Forward), founded in 1897 and still in print, with English and Yiddish versions.

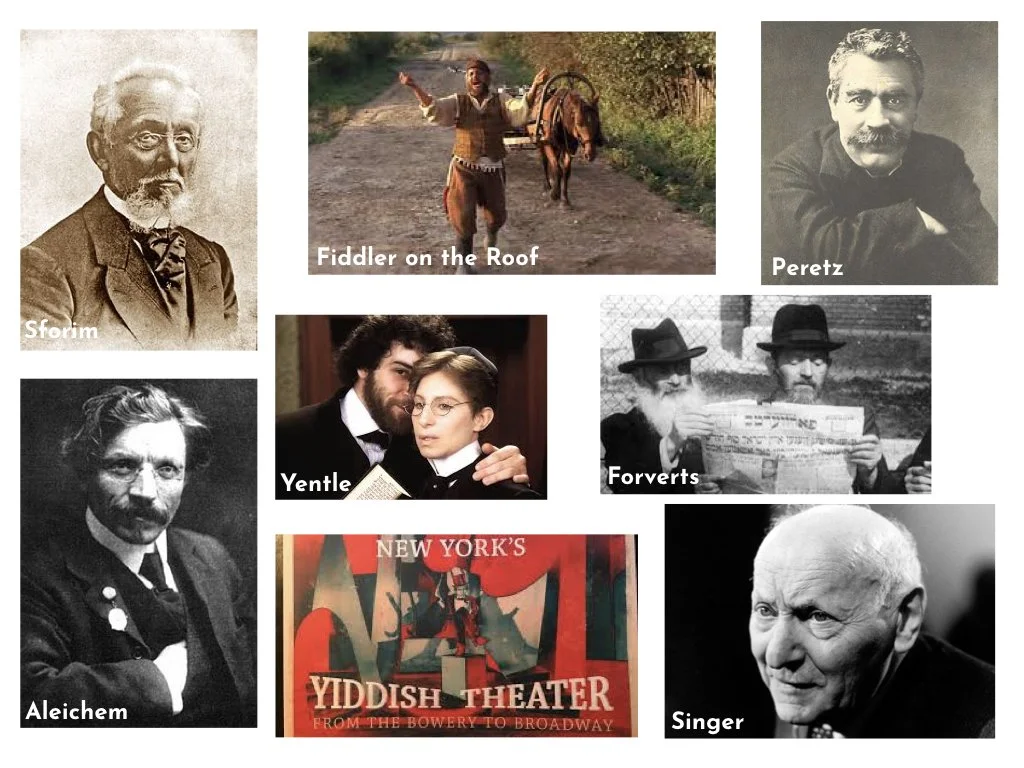

At about the same time, secular Jewish fiction began to emerge in Yiddish. The religious authorities of that time did not approve of these irreverent Yiddish writings, dealing with modern secular and frivolous themes. The first of the great Yiddish writers of this period was Sholem Yankev Abramovitsch, known by the pen name Mendele Moykher Sforim (little Mendel, the bookseller). He wrote stories that were deeply rooted in folk tradition but focused on modern characters. Perhaps his greatest work is his tale of Benjamin the Third, which is thematically similar to Don Quixote. Mendele’s works gave Yiddish a literary legitimacy and respectability that it had not previously experienced.

The next of the great Yiddish writers was Yitzhak Leib Peretz. (I.L. Peretz). Like Mendele, his stories often had roots in Jewish folk tradition, but favored a modern viewpoint. He seemed to view tradition with irony, bordering on condescension. But perhaps the Yiddish writer best known to Americans is Solomon Rabinovitch, who wrote under the name Sholem Aleichem (a Yiddish greeting meaning, “peace be upon you!”). Sholem Aleichem was a contemporary of Mark Twain and is often referred to as “the Jewish Mark Twain”. From here to the Yiddish theatre is but a small detour, and we can well understand the folk tale of Tevye the milkman and his daughters, which was adapted into the musical Fiddler on the Roof.

One last Yiddish writer deserves special note, Isaac Bashevis Singer. In 1978 Singer won a Nobel Prize for Literature, for his writings in Yiddish. He gave his acceptance speech in both Yiddish and English and spoke with great affection of the vitality of the Yiddish language. His stories tended to deal with the tension between traditional views and modern times. Perhaps the best known of his many writings is Yentl the Yeshiva Boy, which was adapted into a stage play in 1974 and later loosely adapted into a movie, starring Barbara Streisand.

The Yiddish Theatre had a major influence on American musical theatre and is clearly woven into the Broadway fabric of the American musical theatre. I will let you find the references.